NEI customer Jobie Hill, a Preservation Architect with an alphabet soup of professional credentials after her name, recently sat down with me to discuss her magnum opus; a culturally vital project with an almost ridiculously difficult scope, simply called “Saving Slave Houses.” As a marketing person, I am often often tasked with making words mean more than the sum of their parts, and in a breath of fresh air, finally, something that is simply called what it is. NEI recently donated some mapping equipment to Jobie to make her journey easier (and a little more accurate). Fortunately, we were able to barter the following Q&A for a single, gently used Trimble Geo handheld data collector. This is her fascinating story.

– Brandy Cavitt, Brand Manager, NEI

Saving Slave Houses

BC: What is your full name and title, and are you affiliated with a particular company on this project, or is it your own gig?

JH: Jobie Hill, AIA, LEED AP, NCARB

Title: Historic Preservation Architect

Affiliation: None. Saving Slave Houses is an independent project I created.

BC: Do you remember where you were the instant that you knew you wanted to embark upon this project? How did the idea develop and what motivated you to pursue this?

JH: The idea for this project came about when I was doing research for my Masters of Science thesis in Historic Preservation, entitled “Humanizing HABS: Rethinking the Historic American Buildings Survey’s Role in Interpreting Antebellum Slave Houses.” After I identified the slave houses in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) collection I contacted State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPO), county historical societies, and other historical organizations across a variety of disciplines inquiring about the individual slave houses in their state. I found that the slave house is not a building type that is consistently categorized or flagged in databases and other various collections. This lack of a systematically compiled database of domestic slave buildings makes comparative studies difficult.

As an effort to remedy this problem I developed the “Slave House Database,” a central repository of information pertinent to all the known slave houses in the United States. I created the framework for the Slave House Database in 2012. Initial beta testing of the database structure began in 2013. The database includes geographic information; owner contact information; local, state and national historic listings; architectural information; completed surveys and documentation; archaeological excavations; census data; and genealogical references. The Slave House Database is a crosswalk for diverse fields (architecture, anthropology, archaeology, historic preservation, genealogy and folk culture) to access and reference. The publishable Slave House Database can be used to identify, locate, analyze and interpret slave houses, as well as connect to other existing resources.

Another motivation for creating the Slave House Database is my desire to integrate data from diverse academic areas into my research and interpretation of the personal lives of slaves. For example, my thesis “Humanizing HABS” utilized the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and the Federal Writers’ Project, two large-scale government survey projects from the 1930s that, in part, documented slavery in America. HABS documented the architecture and created graphic representations of numerous sites. The Writers’ Project recorded American life histories from ex-slaves.

The slave narratives brought to life the spatial density, degree of accommodations, nature of the facilities, and attitudes of those who inhabited the slave house. My thesis research revealed five new relationships between the two collections that were never before made. Five documented slave houses from the HABS collection were directly linked to slave narratives recorded by the Writers’ Project. The relationship between the historical record and the stories of the inhabitants are crucial to our understanding and interpretation of the lifeways and settings of an enslaved people in America. In doing so, the plantation landscape is revealed not through the eyes of the master but through the perspective of those who were in his charge.

BC: What is a typical day like for you ?

JH: On paper, probably not very exciting. But being on site, actually doing the survey, exhilarating! Once I am on site the order of operations is typically as follows:

- Meet and check in with the owner(s)

- Share information about the site that I have with the owner

- Collect any information that the owner has about the site and wants to share

- Walk around the site

- Collect GPS coordinates and fill out Data Dictionary

- Take photographs

- Take measurements

- Sketch site plan

BC: The amount of work seems daunting. What is the scope of your project, and how are you measuring the success of your project? Is it by number of houses mapped, or by some other variable?

JH: The overall scope of the survey portion of the project (which will take years to complete) is to survey all of the extant domestic slave buildings in the United States. To make this undertaking more manageable, I have divided the project up into multiple phases. The success of each phase is measured by the number of sites visited, taking into consideration the willingness of the owners to participate in the survey.

To date, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) collection has been the primary focus of my research and surveys, and, therefore it will be the first collection that I complete for the Slave House Database. HABS has completed over 350 surveys of slave house at approximately 300 sites in 26 states. My goal is to survey all of the HABS-documented slave houses in the United States.

Summers, 2012 and 2013, I was employed as an architect for the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), part of the Heritage Documentation Programs division of the National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior. In September 2013, I conducted a pilot survey project for the Slave House Database with the support of HABS resources and equipment. I worked in consultation with HABS staff to refine my survey methods. At the end of the project I had successfully surveyed fifteen HABS-documented slave house sites in Virginia. I created a report for each building that included the historical significance, a physical description, a brief history and photographs. These reports will be included as an addendum to existing HABS documentation.

I have recently been awarded a research fellowship and a travel grant to continue my research of the dwellings of American slavery. The fellowship is the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH), 2014 We the People Research Fellowship in African American History and Culture through the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The grant is the Stewardson Keefe LeBrun Travel Grant (LeBrun Travel Grant) through the Center for Architecture Foundation in New York City.

The NEH Research Fellowship grants me complete access to the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library’s collections. The primary collection I will research is the Agricultural Buildings Project, an architectural survey project that began in the early 1980s. I will also research the library’s collections for slave narratives, testimonies and other first person accounts from slaves and ex-slaves. At the end of my fellowship at Colonial Williamsburg I will have identified documented slave houses and slave narratives from the Chesapeake to be included in the Slave House Database.

I am using the LeBrun Travel Grant to continue surveying HABS-documented slave houses in the United States, with the goal of completing surveys in the states with the largest number of HABS-documented slave houses. The entire project is expected to take five months and include over 100 sites in the states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia.

BC: What have been your biggest setbacks so far in this project, and how have you overcome them?

JH: The two biggest setbacks so far are:

- Finding current addresses for the sites and owner contact information.

- Not having all the proper equipment to complete the surveys in a reasonable amount of time

Only thirty percent of the sites in the HABS collection have actual addresses associated with them. The majority of the sites, seventy percent, list only a road or intersection in the vicinity of some city. I have been successful in finding more up-to-date site and owner information on the National Register of Historic Places (NR) nomination forms; but only twenty-nine percent of the sites are listed on the NR and twenty-six percent of them are the same sites as the thirty percent with actual addresses. I have also reached out to local historical societies and gotten good results. The three key ingredients needed to overcome this setback are: creativity – to be creative with the resources I research to find the information; communication – reach out to as many people as possible; and perseverance.

Surveying a building alone requires tremendous organization and the use of specialized equipment. Having the proper equipment is crucial to the success of my project for two reasons. First, using specialized equipment allows me to survey a building quickly and efficiently. This, in turn, allows me to complete multiple surveys in one day. Second, the information collected with the specialized equipment meets the standards of other organizations (e.g. Historic American Buildings Survey, Monticello, and Colonial Williamsburg) that I intend to share my data with. I have overcome this setback by reaching out to companies and asking for donations to my project in the form of equipment, software, accessories, and technical support. It is with these very generous donations that I will be able to reach my goals.

BC: Tell us about some of the most exciting discoveries you have made while on this journey.

JH: The top three most exciting discoveries I have made on my journey, thus far, are: subfloor pits, intact items of unknown use, and successful repurposed buildings. Subfloor pits in slave houses are a very curious feature. I have read about subfloor pits while conducting scholarly research. They have been discovered during archaeological excavations, but rarely are they found associated with an extant building. This may because they do not exist or because their existence is unknown. The intact one I have come across was at Pharsalia in Nelson County, Virginia (ca. 1814). The subfloor pit was inaccessible because the wooden floor boards covering it had been nailed down many decades ago. But the owner, a descendant of the founding family, knew about the pit and plans on removing the boards someday to expose the pit. Pharsalia also had an intact item of unknown use (see photo “Pharsalia_Fireplace Item”). In the slave house, next to the fireplace and attached to the wall is a wooden item of unknown use. An original intact item like this is incredibly valuable to our understanding and interpretation of the lifeways of the original inhabitants. Clues to what this item might be may be found in the Slave Narratives.

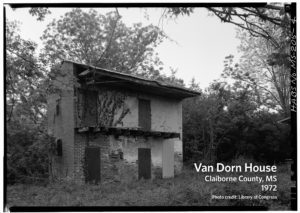

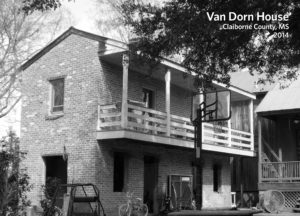

For me, one of the most exciting discoveries I can make is to find a dilapidated slave house from the 1930 that has been repurposed but still retains its integrity. One of my favorite examples of this is the Van Dorn House in Claiborne County, Mississippi (ca. 1830). The owner, a descendant of the founding family, is an architect and is interested in historic preservation. He partially restored the once abandoned, dilapidated slave house and repurposed it into his office.

Van Dorn House – 1972 – Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Van Dorn House – 2014 – Photo Credit: Jobie Hill

BC: How do you plan on getting the word out about your work?

JH: In September 2014, the Slave Dwelling Project is hosting its first national conference. I am presenting the results of my thesis and my surveys at this conference; leading a discussion about the preservation and interpretation of historic slave houses; and exploring how my work affects the general public’s understanding of slavery in the United States. Having seen firsthand hundreds of slave houses, as well as examining them from an interdisciplinary perspective, I will be able to offer an exclusive perspective about the structures and inhabitants of slave houses.

I am also using word of mouth to advertise my project. Every site on my list is an opportunity to meet new people. I come into contact with historical societies during the research portion of the project and I get to meet families and organizations when I am in the field surveying.

BC: Is there anything else you want people to know about Saving Slave Houses? Is there a website where people can find out more information or offer donations?

JH: I want people to know that I am interested in all domestic slave buildings, not just those used exclusively for housing. It was very common for slaves to work and live in the same building. This is especially true for kitchens and washhouse, because these services were in high demand.

Currently, there is not a website. Right now I am focusing on completing my surveys and getting the information put into the Slave House Database. One of my long term goals for this project is a public platform to share the information. But for now, if people would like more information they can email me at: savingslavehouses@gmail.com.

BC: Is this project self-funded?

JH: This project is self-funded but relies heavily on grants, fellowships and donations.

BC: What kind of help and resources could you use to make this project everything it can be, and how should people contact you if they want to help out?

JH: I am always looking for information about existing domestic slave buildings and the enslaved people that lived in them.

I am also always actively looking for donations in the form of:

- Money to cover travel costs (gas, food, car maintenance)

- Equipment

- Lodging

- Technical Support

- Research

The best way to contact me is by email: savingslavehouses@gmail.com

BC: Thank you so much for your time, Jobie. Everyone here at NEI wishes you the best of luck on this amazing project.

*PHOTO CREDITS

| Van Dorn_1972 | 1972 | Library of Congress. Prints & Photographs Division. HABS MS-205. |

| Van Dorn_2014 | February 2014 | Jobie Hill. Slave House Database. |